Atlantis’ Polymorphic Design

By Michael McCormack

Atlantis is a networked organization that is hosted in the Atlantic regions of the unceded, unsurrendered lands of the Beothuk, Mi’kmaw, and Wolastoqiyik peoples, as well as the Inuit, the Innu, the Southern Inuit of NunatuKavut. As an artist, curator, and descendant of settlers to this region, I am eternally grateful for the generosity, wisdom, and perseverance of Indigenous water protectors who continue to lead with strength on the frontlines of environmental and political crises in the Atlantic. With the flooding of the reservoir at Muskrat Falls, and the Alton Gas developments on the Shubenacadie River, settlers have so much to (un)learn with regards to water protection, environmental ethics, and territorial sovereignty.

Water lends itself well to metaphors of flexibility and turbulence. When Atlantis was planning a conference we envisioned a flotilla as a mode of gathering—this loose network of vessels could operate autonomously, while still staying tethered to one another. It is important that water was not just metaphorically referenced at Flotilla, but that various artistic projects at Flotilla criticize the dire sociopolitical climate around water privatization and pollution in the Atlantic provinces.

Lindsay Dobbin facilitated a deep-listening project about the Floating Warren Pavilion. Inviting visitors to listen to the water through an underwater microphone, Dobbin asked “can we mirror the living water in how we move, learn and create?” Click the photo to listen. Photo: LP Chiasson & Festival Inspire.

Atlantis is an association of artist-run centres that is sprawled across the four Atlantic provinces on the east coast of Canada. When this small association proposed to host an ambitious national conference, it was clear that we didn’t have the capacity to run an event in the same way as large-scale organizations. No, that simply would not have reflected of our way of working together on the East Coast—on shoestrings, in DIY spaces, in geographically dispersed communities.

After over forty years of adapting to federal and provincial funding systems, the contemporary Canadian art sector has become increasingly bureaucratic. Alternative arts spaces have slowly professionalized since the late 60’s, and have arguably become even more rigid in structure than some public galleries and museums.[1] Many Atlantic organizations have departed from their “Gallery” title such as Eyelevel, Third Space and ConneXion ARC, as they continue to go through a restructuring period, attempting to broaden the scope of how they present contemporary artists work. The Centre For Art Tapes is another organization who completely restructured their administration to include a non-hierarchical, lateral framework.

Flotilla marked the first time that the biennial gathering of artist-run centres took place in Mi’kma’ki, on the unceded territory of the Abegweit First Nation, recently referred to as Charlottetown, PEI: The Birthplace of Confederation. Flotilla took place alongside celebrations of 150 years of colonialism, as well as the 50th anniversary of Canada’s bureaucratic arts system. At Flotilla, it was timely and appropriate to question the very structure that artist-run centres were brought up in, given that so many centres flourished under the systems of arts funding which have been in effect since the centennial celebration of colonialism in 1967. The lack of available funding in the Atlantic encouraged Atlantis to pursue more experimental programming initiatives at Flotilla. The gathering took place in a province which had recently dissolved its arts council, and in a city with only one artist-run centre, which at the time had never received operational funding.[2] These spatial and financial limitations encouraged Atlantis to create new temporary pop-up spaces installations, performances, and artist-run initiatives that otherwise would have been centralized into established venues and centres.

The organizational structure of Flotilla intentionally mirrored the collaborative and improvisational style that was necessary to carry forward and support projects that were more interactive in nature. It was important that our team allowed each contributing artist and organization to become polymorphic. Projects were conceptually tethered to one another, but were allowed to mutate and adapt in their own way, to take on their own form leading up to and during the four days of Flotilla. Flotilla’s Project Lead Becka Viau, along with the Steering Committee, Core team, and Curatorial Team all kept this in mind throughout the development of the program.

Throughout the planning of Flotilla, Atlantis lifted traditional conference structures away, allowing us to reconsider our bureaucratic tendencies and restructure the foundation of our programming from scratch. When peeling away the layers, we were able to examine how we have function as artist-run centres, organizations, and individuals, and in doing so we revealed many of our dependencies on institutional structure. Reflecting on this allowed us to identify our flaws and contradictions, re-generate new ideas, and foster radical thought. We challenged ourselves to prioritize accessibility, inclusivity, and safe(r) spaces, acknowledging multiple generations and communities as valuable contributors to artist-run culture. We challenged ourselves to expose the ways in which Flotilla was bound to fall short. Flotilla provided a temporary emancipation for artists from decades of administrative centralization, even if for only a few days. This was made possible through thousands of hours of preparation and hard work from regional and visiting artist-run centres, multiple levels of public funding, and an extremely talented and supportive community. The results, we hoped, would create a platform for smaller artist-run centres who service isolated, dispersed, and marginalized communities to showcase their work, offering long overdue recognition for underrepresented artists and their communities.

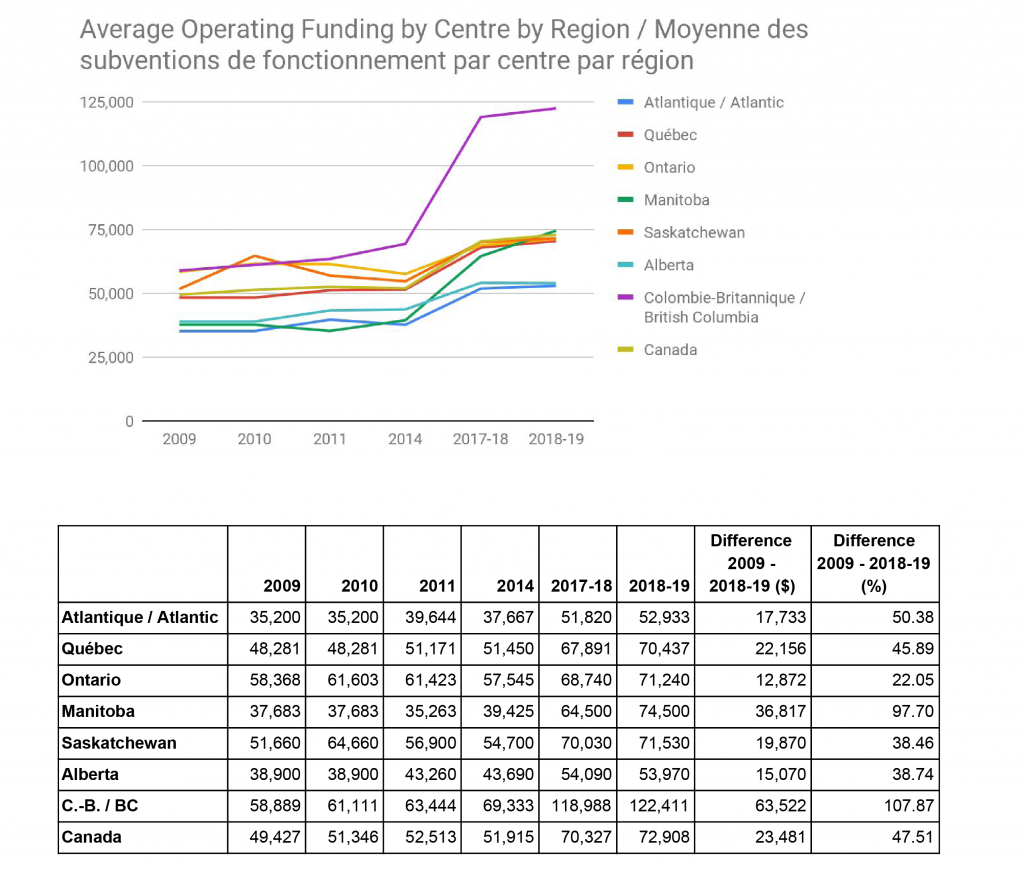

In the 2012 Burgess Report on The Distinct Role of Artist-Run Centres in the Visual Arts Ecology, Atlantic Canada is identified as a region that has consistently received low and uneven distribution of funding. The Burgess Report establishes a clear difference in impact between centres in the Atlantic region, which have suffered from a consistent lack of regional support over the past 40 years, and centres across Canada with consistent provincial support.[3] The Burgess Report states that “there are regional factors to consider in the funding of ARC’s. In particular, the low funding levels to ARC’s in Atlantic Canada limits their ability to play a more significant role in the local ecology.”[4] Amanda Shore expands on this topic in her 2017 paper titled “A Place About Now: Floating Architecture & Utopic Imagination in Atlantic Artist-Run Culture.” Shore conducted extensive research on Flotilla through interviews, observations, and her involvement in Flotilla as a writer and Programming Coordinator. In the section of her paper on geographic marginality, she identifies multiple forms of sociopolitical marginality; isolation within the borders or structures that have been laid out by colonizers, politicians and bureaucrats, as well as through racial, economic, environmental, and linguistic inequalities.[5] Shore also highlights an important observation in the Burgess Report—that “Atlantic Canada lacks an Aboriginal ARC. Similarly, there is no Acadian art institution in Halifax, and it is believed that an Acadian ARC would help advance the discourse and be good for artists and the communities.”[6]

There is no doubt that centres in all four Atlantic provinces have suffered from the lowest revenues in the country. The Burgess Report, following the 2009 study Employment Standards in Canadian Artist-Run Centres and Independent Media Arts Centres show evidence of consistent lack of support for Atlantic ARC’s for over four decades. Most Atlantic artist-run centres are the only artist-led organizations in their communities, and they have the potential to serve a broad spectrum of artists from a variety of backgrounds and media.

When Atlantis was selected as the host for the 2017 national gathering of artist-run centres, our membership felt mixed emotions of excitement, fear, doubt, and inspiration. Up to this point, the task of hosting an event of this scale was not beyond our capabilities, but beyond our administrative capacity given our resources. Flotilla opened our imagination, and in turn proved that given the opportunity, our underfunded organizations had tremendous potential to collaborate as leaders in our scattered communities across the Atlantic.

Our fifteen artist-run centres are interspersed across communities with differing political climates, funding structures, and cultural histories, and therefore it was important that each project within our programming remained relatively autonomous and distinct.

The Flotilla metaphor applies both conceptually and literally to our communities mutually bound by water. The Flotilla model serves as a reminder that we must trust in each participating artist and organization, in order to make space, share power, and allow for flexibility within each branch of our programming. With our polymorphic design we are suddenly able to adapt, and encourage projects to remain spontaneous and responsive, in real time, as interactive components, and all as autonomous vessels.

[1] For more research on the professionalization of artist-run sector, see Clive Robertson, Policy Matters: Administrations of Art and Culture (Toronto: YYZBOOKS, 2006).

[2] PEI’s artist-run centre this town is small has run many large-scale events such as Art In The Open since 2010, but had only received project funding until after Flotilla, when it was finally granted federal operational funding.

[3] Three examples are: Lattitude 53 in Edmonton, AB, Plug In ICA in Winnipeg, MB, and Mercer Union in Toronto, ON, all of which have been around as long as Eyelevel Gallery, but in regions where support for Artist-Run Centres is particularly high.

[4] MDR Burgess Consultants, “The Distinct Role of Artist-Run Centres in the Canadian Visual Arts Ecology” (Ottawa: Canada Council for the Arts, October 13, 2011), 44.

[5] Amanda Shore, “A Place About Now: Floating Architecture & Utopic Imagination in Atlantic Artist-Run Culture” (unpublished paper, 2017).

[6] MDR Burgess Consultants, “The Distinct Role of Artist-Run Centres,” 44.